This morning, a new pupil reminded me of myself when I was 24 years old and learning the clarinet.

This morning, a new pupil reminded me of myself when I was 24 years old and learning the clarinet.

Life events took me to Windhoek in Namibia for a year soon after finishing university. I decided to take up the saxophone, which is something I’d always wanted to be able to play. The Windhoek Conservatoire had no saxophone to lend me, so I settled on the clarinet – “it’s a similar instrument,” I was told.

After a couple of weeks I told my teacher I planned to be able to play Mozart’s clarinet concerto by the time I left the country. She looked at me nonplussed but was too polite to set me straight. In a few more weeks I realised how naïve my expectations had been.

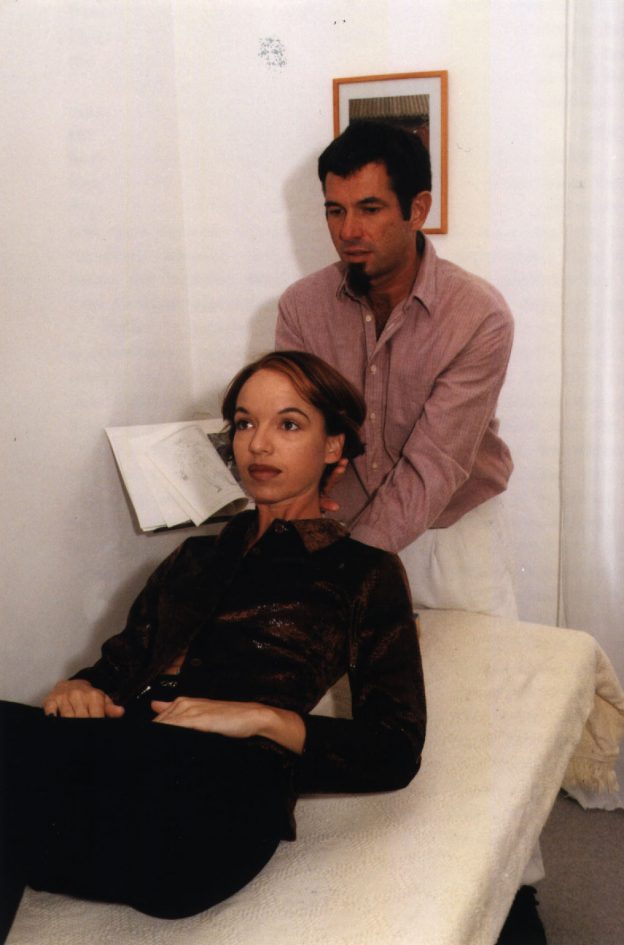

So this morning, my pupil asked me: “What’s the longest-standing pupil that you have?”

“Over 5 years in a couple of cases,” I replied, “and there is one pupil whose recently returned after I first taught him over 20 years ago.”

“What?” she asked looking over her shoulder at me. “What can there possibly still be to learn after all that time?”

I smiled remembering my own assumptions about the clarinet – after all, I’d thought, you only play one note at a time, it couldn’t be as difficult as the piano which I’d played as a child.

Pupils can make extraordinary progress in just 10 Alexander lessons and really enjoy surprising benefits in that time. But like any skill in life that is really worth learning, it may take a good deal longer to get good at. Socrates said something like: ‘The more I learn, the more I realise how little I know.’ And how much more true is this when it comes to learning about ourselves!

Becoming a teacher of the Alexander Technique takes three years of full-time training. Even after that, novice teachers frequently don’t feel up to the job. Malcolm Gladwell in his book Outliers wrote that it takes 10,000 hours to become seriously good at anything. While one doesn’t need anything like that to benefit hugely from the Technique, I must admit it was only after I’d been teaching for about 10,000 hours that I really did feel like an expert at teaching it.

© 2017 Barry Kantor