I used to feel dulled, clouded and veiled in most of my daily life. Or at least that’s how I now perceive it, after my experience of the Alexander Technique. Days that embarrass me to look at photographs of that time – round-shouldered, pulled into myself, down and heavy.

I used to feel dulled, clouded and veiled in most of my daily life. Or at least that’s how I now perceive it, after my experience of the Alexander Technique. Days that embarrass me to look at photographs of that time – round-shouldered, pulled into myself, down and heavy.

‘Out of touch’ best describes it. Out of touch with my body, myself and the world around me, to say nothing of others. It is hard to explain this difference to anyone who has not had this dramatic shift in perception and awareness. I suppose that I didn’t realise what my state of being was like. It was so much part of me and I had no clear mirror on what was going on. The way we feel and think governs the way that we see things; and it is difficult to get an outside perspective on ourselves.

In those dull days I would often get frustrated and angry. I would react to small things, and lacked patience. I would always be rushing. Sometimes, I would get into arguments before I knew what was happening.

At the same time I was working as an attorney in a hectic office with five secretaries and could not possibly monitor all their work. The strain was enormous. I was also unfit because I had no time and frankly used to hurt myself when I rushed into exercise. Also, my coordination was bad; I could never see the ball let alone hit it. To make things worse, I was painfully insecure.

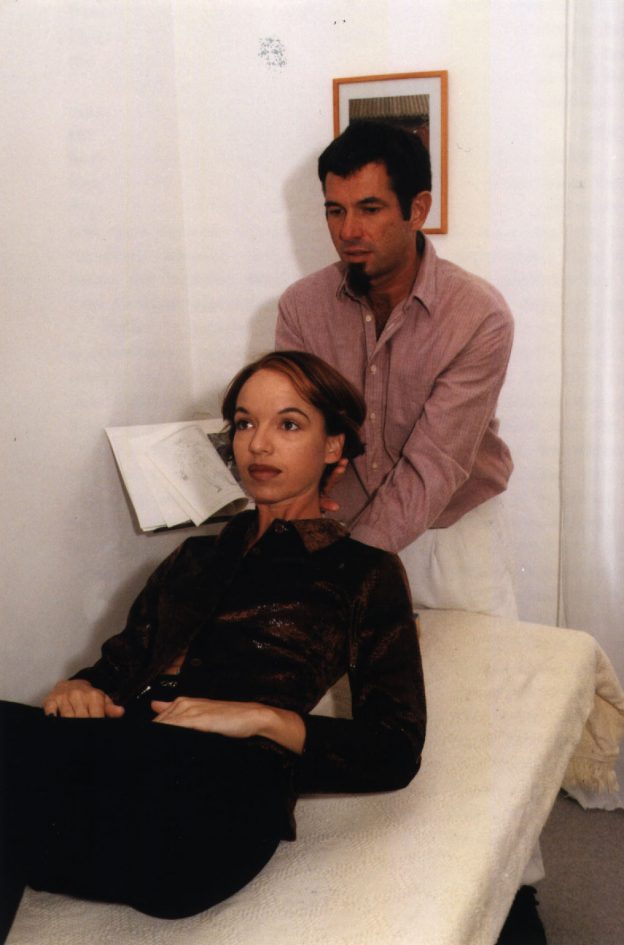

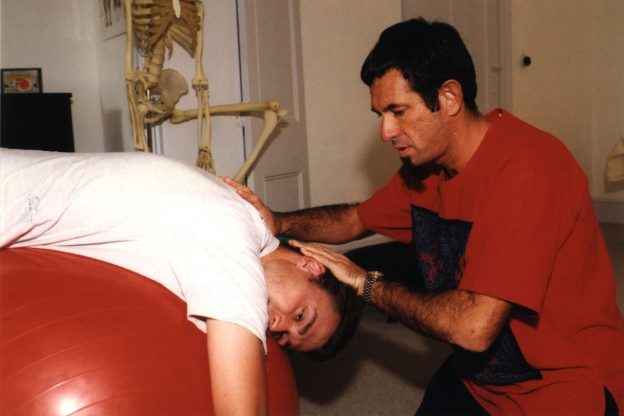

One day a friend suggested that the Alexander Technique would help me to straighten my back. I had always found that straightening up meant painfully holding myself up and I could never sustain it for more than a few minutes. I thought it would be wonderful if this Technique could work. My first lesson meant very little to me. I could get no sense from the teacher what I was supposed to do. I felt very little happening. I went again just to make sure. In my second lesson, while my teacher was working with me on her table, I was surprised to find myself becoming emotional. I knew that something important was happening. Out of touch with my emotions as a rule, this felt like the softening of a lifetime. Over the next few lessons I became aware that my posture was changing very slightly and I made the connection between how I was reacting unconsciously out of my emotional state and my physical condition. Mostly, at first, I found I was beginning to let my shoulders drop – I’d been unaware how I’d been holding on as a result of tension. I became aware of the possibility of changing my posture but also aware of how difficult this was going to be. I was told very little by my teacher and felt that I was being kept in the dark. The whole process was a complete mystery to me and I regret now that my teacher couldn’t give me a clearer idea of what was happening. What was clear was that Alexander Technique had to do with a lot more than just my posture.

After about 20 lessons I went abroad trying to forget law. I spent the next year in a campervan in Europe and thought a lot about this new technique that I had learnt. Life became easier and I had a great time. But I was still not at all happy about my posture. Nevertheless, I did feel that I had a tool to help me to improve it.

When I got home I found that I still had no solution to my dreadful work life. I went back to law and after several months of time-wasting delay, back to Alexander lessons. Now the hard work really began. I felt so wonderful after a lesson but by the next day I needed another one. This cycle continued for several years before I found the courage to admit that I did not want to be a lawyer. Instead I wanted to conquer my indecisiveness, become more true to myself in everything that I did and sort out the physical problems that I had had all my life – poor breathing, lack of coordination and shocking posture. I had already discovered that my posture was a reflection of the way in which I saw myself rather than the way I was born. The solution, to study to become an Alexander Teacher was already there, and eventually I found the strength to act on this insight.

Meantime, I had already met a visiting Alexander Technique teacher from London, who had visited Cape Town to give Alexander workshops. His work inspired me so much, he explained so much more, my response was so much more vivid. I sold everything I had, cashed in my insurance policies and borrowed the rest.

Soon I was living the life of a student again, but learning from a deeper place than purely a mental one; where I was embodying my learning. I found, for a change, that I was a good student . I cannot give a fair account of the joy and hope with which I began this venture. It was heaven. Starting at the Centre for Training in Holloway Road was like starting at the bottom. The school was a fascinating playground for exploration, with visiting teachers from near and far, and our wonderful trainer with his magical skill. Soon enough, I was part of a lunch group, and enjoying afternoon teas with my fellow students. These times were important meetings where we discussed the Technique at great length – so the learning day was much longer than the four hours of actual formal school practice.

This continued for the full three years of the course and I greatly missed the sun and the beaches and the space and the friendliness of home. The compensation of feeling that I was on the threshold of mastering the greatest discovery of the century was enough for me. I was growing taller and broader and my shoulders were dropping permanently and moving wider away from each other – my neck emerged like a tortoise’s. I was becoming physically lighter in myself and enjoyed the occasional games in the park with my schoolmates with a ball or bat. I began to cycle to and from school through the wet, gray streets, dodging aggressive, cycle-hating drivers. I began to feel alive and human. I began to enjoy the people around me, learnt to inhibit my negative reactions to perceived sleights and cancelled trains, and was less bothered by things that would have irritated me in the past.

A few experiences at school were especially significant. There were lessons in which I felt completely connected to the whole of my environment and not at all separate from those around me. I was completely flexible and movable and fluid. Time opened up into infinity. Running and other activities were joyful and effortless. I had found my self.

There were of course many occasions when I would feel frustrated with my progress, aware only of how far I still had to go and locked into certain habits that I couldn’t even properly appreciate let alone begin to avoid.

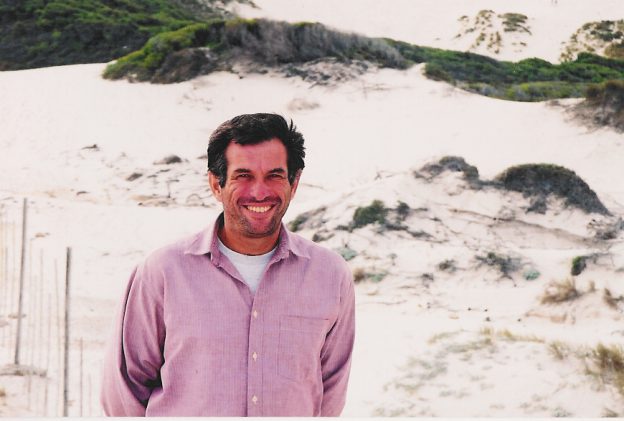

I left London by and large a new person and keen to return to Cape Town to share what I had learnt.

There are times when I feel light and easy. There are times that I am aware of the effortlessness of things compared to what they would have been years ago. There are moments with my pupils when I am in awe of the grace and openness that we are capable of as humans. I feel deeply privileged to be able to work in a caring way, helping others become more mindful, less stressed, calmer, more ‘choiceful’, and with fewer aches, pains and frustrations. My struggles with myself, and the difficulty with which I learnt the Technique, especially in the early days in Cape Town while still practicing law, are now something my pupils benefit from. They seem to learn so much more quickly than I did.

© 2017 Barry Kantor

This morning, a new pupil reminded me of myself when I was 24 years old and learning the clarinet.

This morning, a new pupil reminded me of myself when I was 24 years old and learning the clarinet. I used to feel dulled, clouded and veiled in most of my daily life. Or at least that’s how I now perceive it, after my experience of the Alexander Technique. Days that embarrass me to look at photographs of that time – round-shouldered, pulled into myself, down and heavy.

I used to feel dulled, clouded and veiled in most of my daily life. Or at least that’s how I now perceive it, after my experience of the Alexander Technique. Days that embarrass me to look at photographs of that time – round-shouldered, pulled into myself, down and heavy. Do you have clarity in how you go about things, in your daily tasks, your movements, your thinking? Or are you like most people at the mercy of your reactions, a prisoner of your habits. These can be habits of thought, of posture, and of personality. They are more honestly called your idiosyncrasies or eccentricities. And not all of them are endearing or helpful. You may like to think that this is what makes you you, but actually these habits hide you from yourself.

Do you have clarity in how you go about things, in your daily tasks, your movements, your thinking? Or are you like most people at the mercy of your reactions, a prisoner of your habits. These can be habits of thought, of posture, and of personality. They are more honestly called your idiosyncrasies or eccentricities. And not all of them are endearing or helpful. You may like to think that this is what makes you you, but actually these habits hide you from yourself.